If you find a British establishment with the word dragon in its name, it is likely that you will also find a local legend about a beast lurking in the shadows nearby. A pub called The Dragon, Colgate is no exception. It is close to St Leonard’s Forest in Horsham, a location associated with the prototypical story about a saint slaying a dragon. St Leonard himself cannot truly be claimed as a Sussex saint, but according to folklorist Jacqueline Simpson in »Folklore of Sussex« (The History Press, 1973/2009) returning crusaders often revered this sixth century hermit from France. A long-standing legend suggests that at some point he actually lived in St Leonard’s Forest and even killed a dragon there.

Fake news out of Sussex?

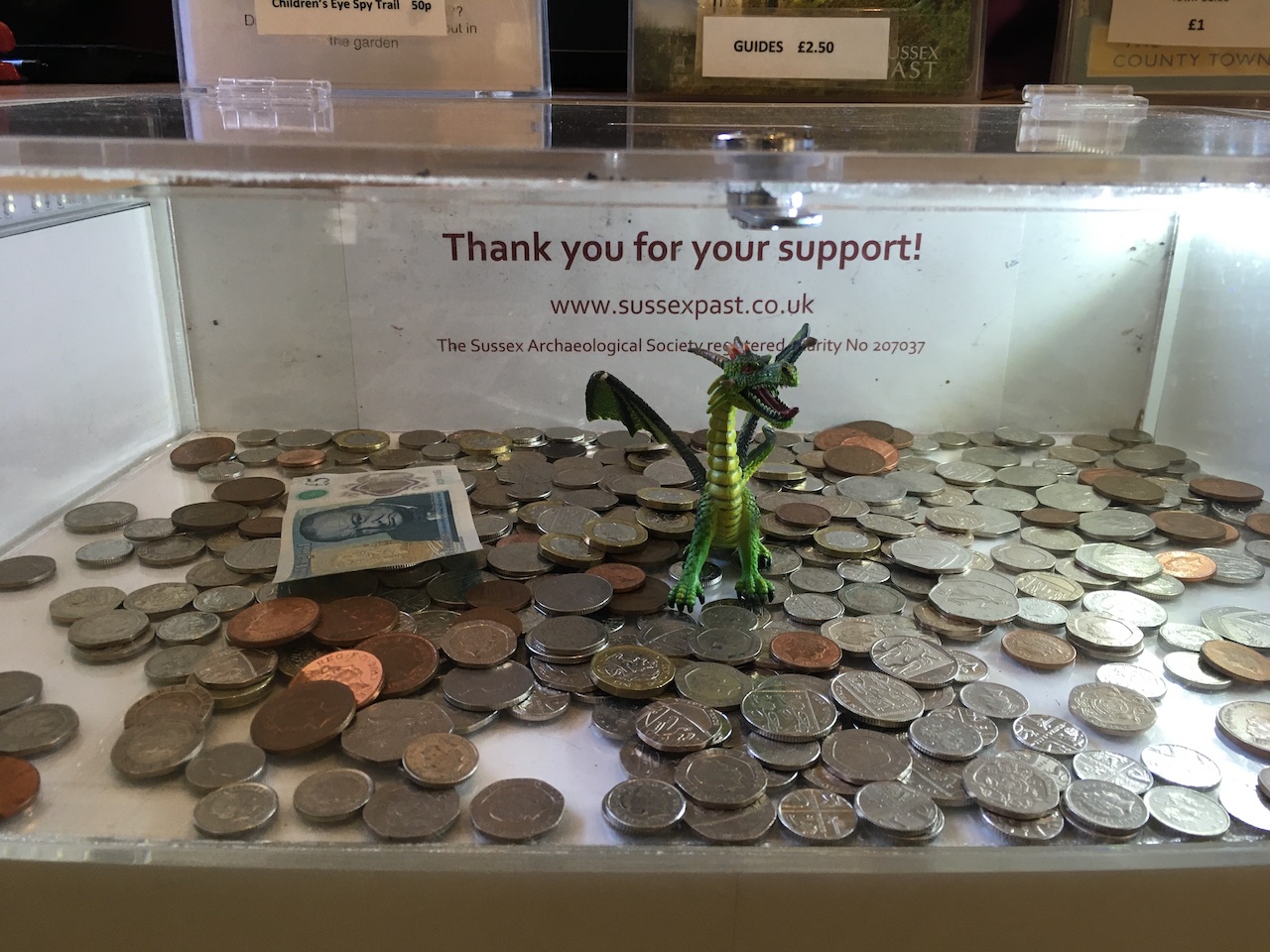

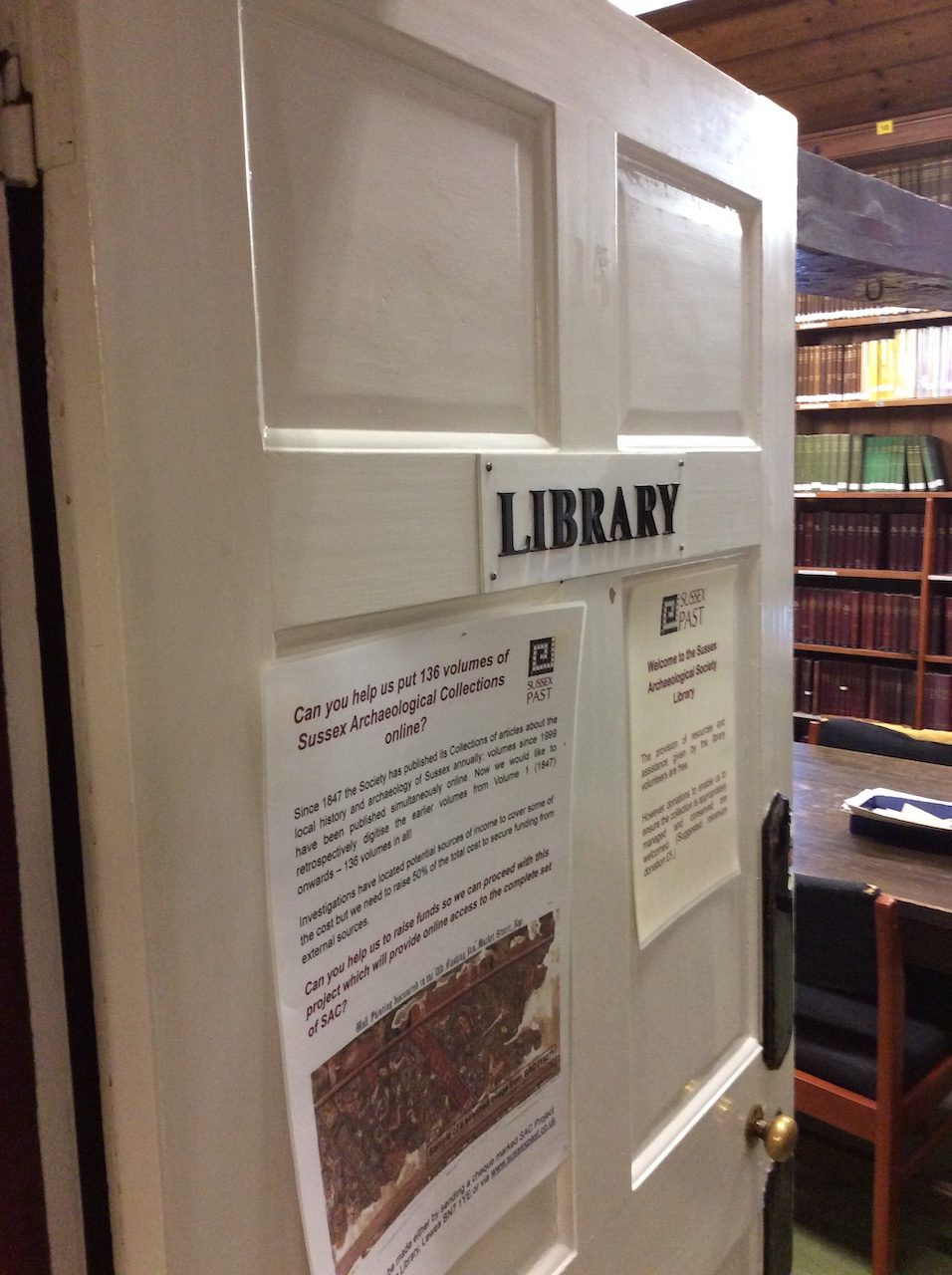

As is often the case with folklore, original sources are scarce, but on a sunny afternoon in October I find myself on a bus bound for Lewes. It is the county town of East Sussex and also the home of The Sussex Archaeological Society. Behind a wooden door on the top floor of Barbican House Museum, just opposite the Norman castle, is the specialist library. I’m late for my appointment, but two volunteers are kindly waiting for me with a pile of books about the local dragon legends of the area.

An account, originally printed by John Trundle in 1614, refers to »a strange monstrous serpent or dragon« that is supposed to have slaughtered both men and cattle in the woods near Horsham.

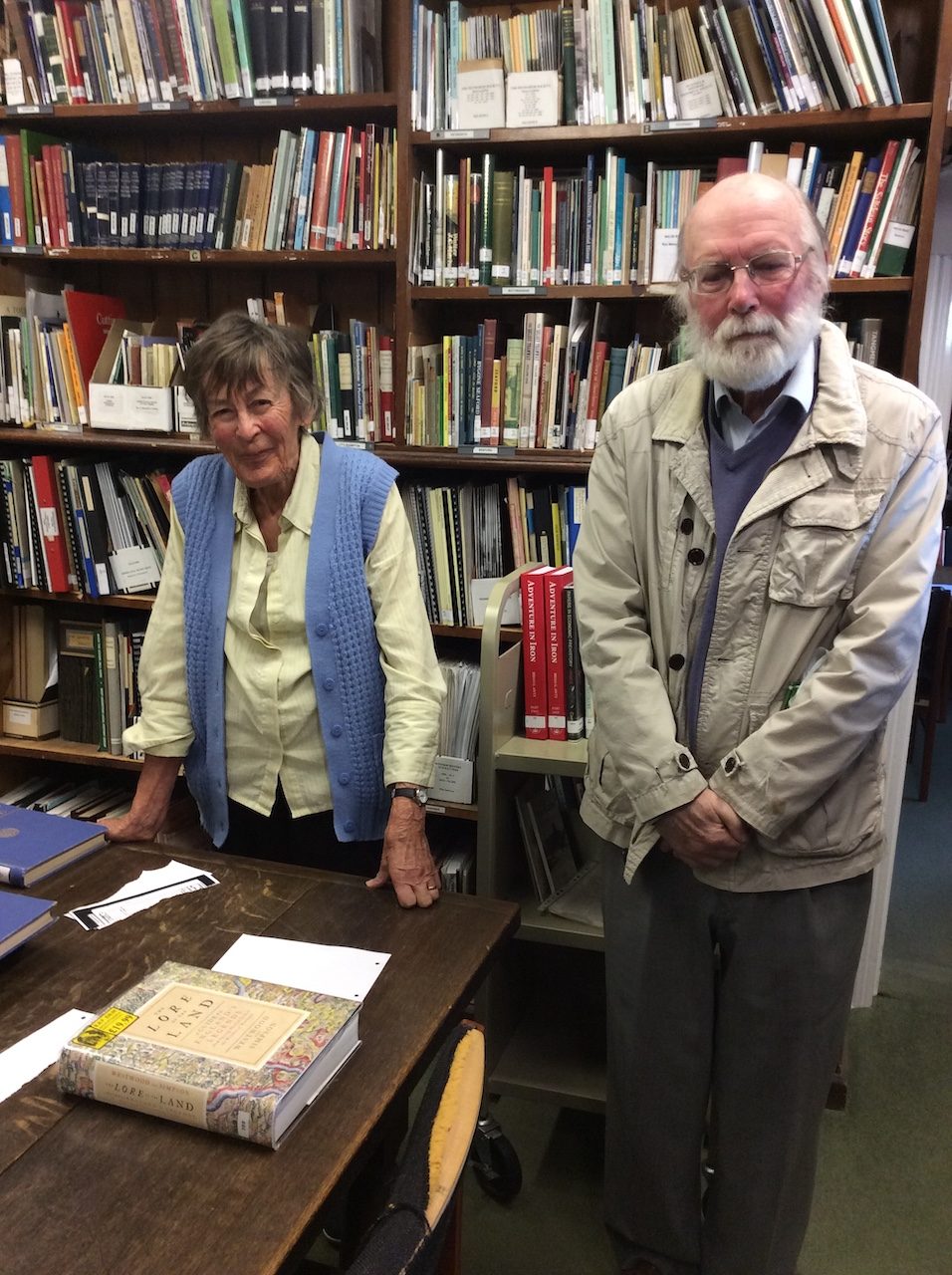

An account, originally printed by John Trundle in 1614, refers to »a strange monstrous serpent or dragon« that is supposed to have slaughtered both men and cattle in the woods near Horsham. »This is the urtext«, says Colin Brent, pointing at the above quote in an old book from 1836, while concluding that the rest of the speculative statements to be found in the library simply retell the same story over and over again. He used to teach history at what is now called the University of Brighton and has been a member of The Sussex Archaeological Society for fifty years. Along with his wife Judith, a retired archivist, he now volunteers to keep the library collections alive and available to visitors.

The serpent (referred to by some as a dragon) was reported to have been over nine feet long and wider in the middle. It is possible that the account of the dragon is a journalistic hoax, as sensational pamphlets were quite common at the time. Another example of this »fake news« phenomenon would be a booklet from 1669 entitled »The Flying Serpent, or, Strange News out of Essex«. As late as in the beginning of the 19th century it was still commonly believed that a monstrous snake haunted St Leonard’s Forest. There might however be a natural explanation behind this enduring myth. According to the antiquarian Mark Antony Lower the idea of a local beast was encouraged by smugglers, who wanted to keep people out of the woods.

The archaeological society’s…

library in Barbican House Museum.

Volunteers Colin and Judith Brent.

Lewes Castle, a Norman monument.

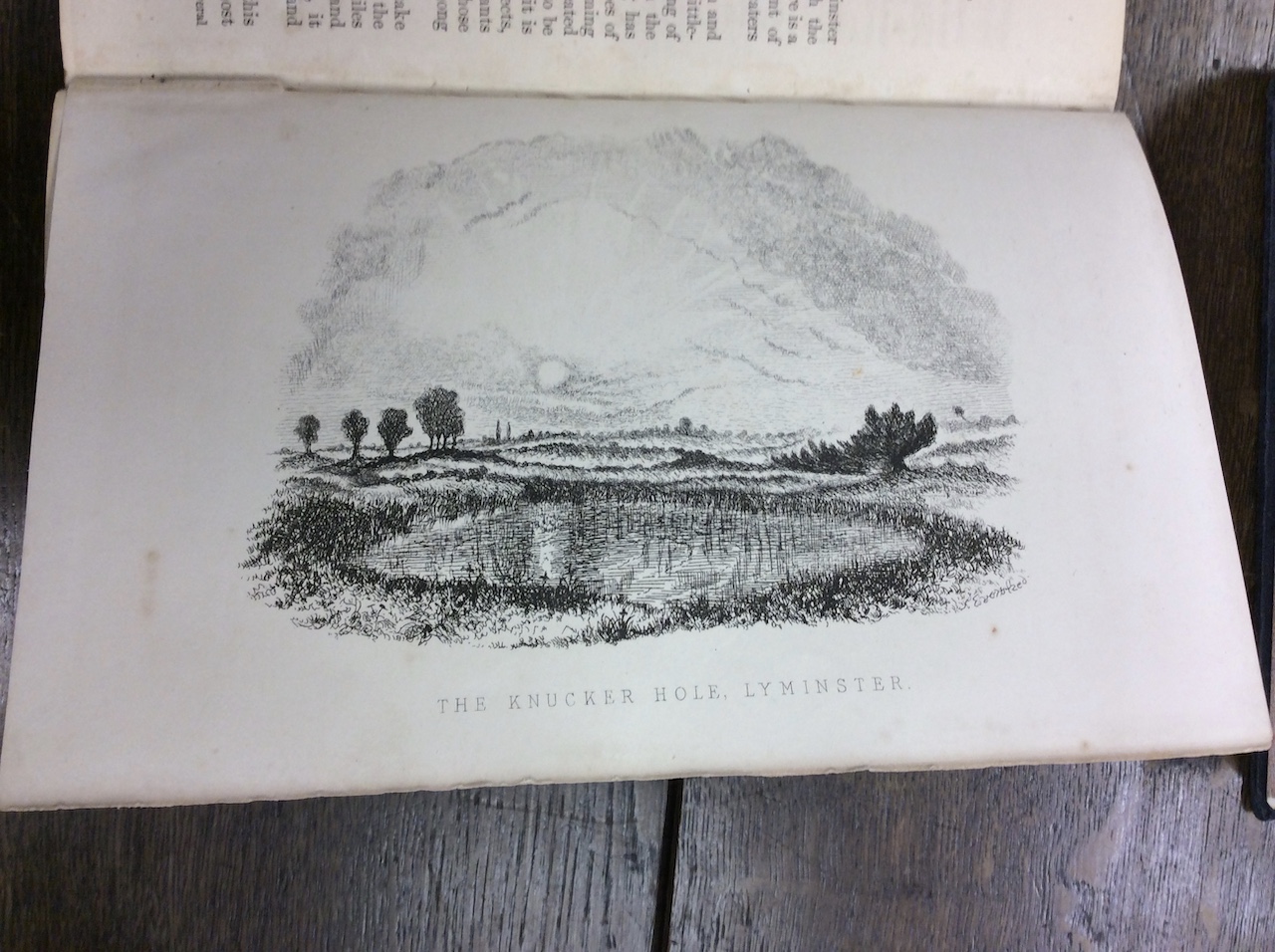

The Knucker of Lyminster

Another famous Sussex dragon is described as a water-monster, who lived in a reputedly bottomless spring or pond near the church in the village of Lyminster. This legendary beast is known as the Knucker and its dwelling-place referred to as the Knucker Hole, comparable to some sort of sinkhole. As Jacqueline Simpson points out, the name Knucker or Nucker descends from the Anglo-Saxon word nicor, meaning water-monster. This is of particular interest to Swedish readers since the word is also related to Näcken, a supernatural being known for playing the violin, thus luring people to drown in his river.

There is a heroic tale about a knight slaying the Knucker of Lyminster, but one of the more popular versions tells the curious story of Jim Pulk. He was a local farmer’s boy, who killed the dragon by poisoning the poor creature with a pie and then cut its head off. Unfortunately Pulk forgot to wash his hands before celebrating his deed with a pint at the pub and accidentally poisoned himself when he wiped his mouth. Talking about beer, what’s the story behind the seasonal ale Georgian Dragon brewed by Harvey’s in Lewes? Well, the artwork features an Iguanodon skeleton as a reference to the local doctor and palaeontologist Gideon Mantell. He was one of the first to publish theories on his fossil findings of the South Downs.

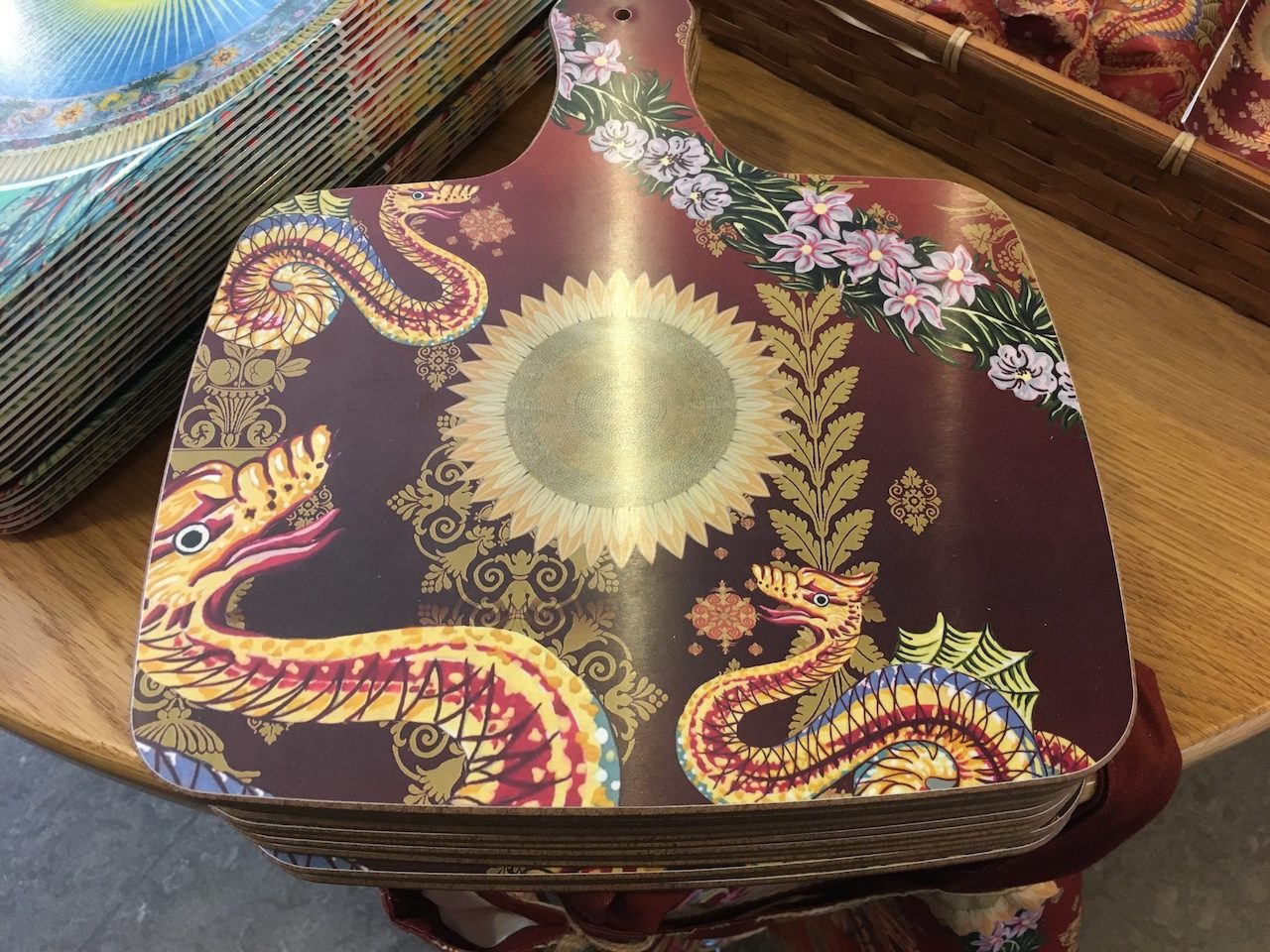

The dragons inside the pavilion are fine examples of Chinoiserie, the European interpretation of Chinese aesthetics popularized by the influx of Asian goods such as porcelain and silk in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Dinosaurs and dragon’s teeth

It is believable that these findings of fossilised prehistoric reptiles at the beginning of the 19th century sparked a renewed interest in both the folklore and the power of dragons. King George IV was so fascinated with these creatures that he had them embellish walls, floors and furniture in The Royal Pavilion. Completed in 1823, his seaside pleasure palace in Brighton was designed to be a Far Eastern fantasy and is known for its striking oriental silhouette.

Photo: Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Photo: Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Photo: Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

The dragons inside the pavilion are fine examples of Chinoiserie, the European interpretation of Chinese aesthetics popularized by the influx of Asian goods such as porcelain and silk in the 17th and 18th centuries. Thus, many of the dragons here are portrayed with wings unlike the Chinese dragon, commonly depicted as snake-like creatures with four legs and viewed as a symbol of power rather than a threat. One of the most impressive objects is the large dragon on top of the chandelier in the banqueting room, but everywhere you look there are dragons. In fact, our guide even encouraged us to look for the winged beasts during the tour, as the dragons also tell us something about the functions of the different rooms.

If you head out to the chalk downlands you might also stumble upon some sharp objects, quite different from the first puzzling tooth found in the region by Gideon Mantell (or possibly his wife) in 1822. During the Second World War, Cuckmere Valley was identified as being a potential landing site for German troops. To prevent invasion by obstructing access from the sea, different obstacles were placed out in the area. Among them is a row of concrete anti-tank blocks known as dragon’s teeth.

The above text was produced during a two week English course for journalists at The English Language Centre in Brighton. I thank the Swedish Union of Journalists (SJF) for the scholarship.